✍️ Rise above the Slush Pile

or, Lick Your Wounds by Licking Ice Cream

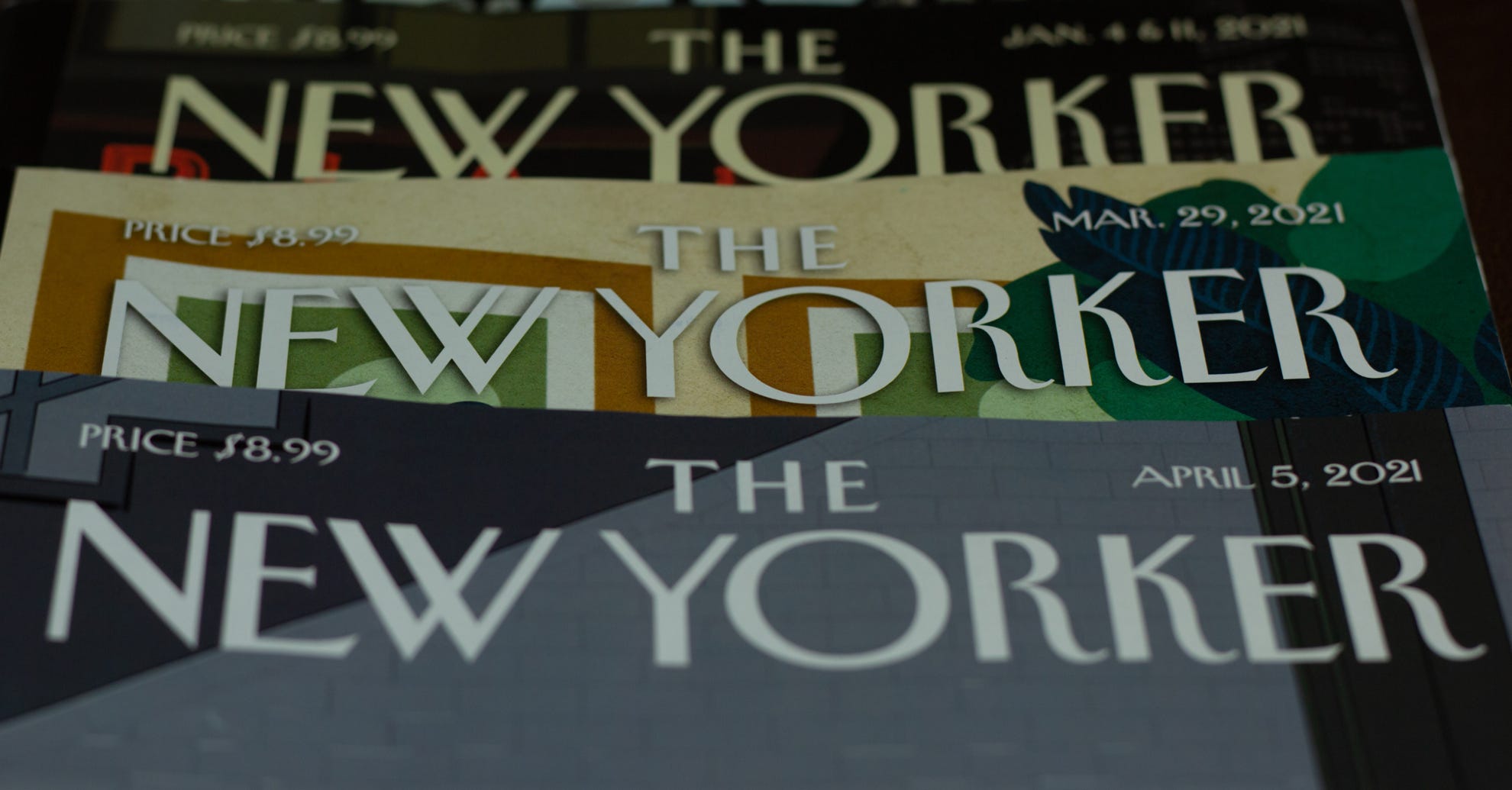

I don’t really like The New Yorker, much as I want to.

Normally, the magazine’s firm stance on the diaeresis and the way they spell “traveller” and “fuelling” would be all it takes. To me though, The New Yorker is like this speciality ice cream store that’s exciting from the outside with turrets and glitter, but inside the menu lists flavours that I don’t care for like Banana or Tomato. Sure, there’s the occasional Elk Crossing that I eat up. “Moving On, A Love Story” by Nora Ephron leaps to mind. But other than those occasionals in traveller cones, it’s a lonely place for me. (And why shouldn’t it be? I’ve lived in New York City a total of about 100 hours in my life.)

On the other hand, I am a sucker for magazine documentaries. Docs about Rolling Stone and Cream were both great. As was the one on Playboy and Hugh Hefner, which was a multi-part series – though for the record, I only watched that one for the articles.

So when Netflix came out with its documentary by Judd Apatow about The New Yorker at 100 years old: sure, I turned it on when I stepped onto the treadmill.

This essay isn’t going to devolve into a review, other than to say that I thought it was well done and worth the watch. But it did spark an idea for me about the misconceptions of the slush pile.

At one point in the doc, the fiction editor explains how she gets 7,000 to 10,000 short fiction pieces per year. Over those 12 months, they publish 50. That’s 0.005% to 0.007% of submissions. There’s a similar segment about cartoon submissions that (ahem…) illustrates the process of the slush pile nicely. Tuesdays are cartoon review days, and the cartoon editor chooses 60 cartoons from the 1,000 to 1,500 she gets each week. Then, she and the Editor in Chief cut that down to 20. You can see them reading, laughing (or not), then putting it into one of three baskets: Yes, No, Maybe. It’s that simple.

I think most of you have the moral of the story already. But let me underline a few things.

Writers can’t take this process personally. Magazine editors aren’t “gatekeepers” who are determined to let certain writers in and keep other writers out. Instead, they are curators, trying to find the best of the best for their readers. They also have personal biases – some like banana ice cream, but others don’t. Therefore, which desk your banana ice cream lands on counts.

We can probably safely assume as well that there are more than 0.005% of stories that are worthy of The New Yorker. However, there are other things at play, too. Known writers will get chosen over unknown writers; if I could read just one story in an issue, I’d pick the one by Nora Ephron. You have your favourites, too. Some stories submitted this month will be too similar to stories published last month. Some will be like French Vanilla: close seconds for almost everyone, but nobody’s first. (The lesson here for me: don’t write French Vanilla. Write Banana and hope it lands on the right desk.) Even if my story is in the top 1% of all stories submitted, it’s still a long shot that mine will be published in The New Yorker.

Thinking about it this way actually comforts me. Sure, I’d like my story to be in that 0.005%. But if it’s not, it’s nothing personal.

The only thing to do is say, “Thank you for reviewing!”, move on, and submit to another magazine. This philosophy holds true whether you’re writing fiction, non-fiction, or poetry, submitting to publishers, agents, or contests.

Oh, and have some ice cream.

~Graham

email me if you get lost.

I have mixed feelings about The New Yorker. I used to read it cover to cover (that's when I had a commute!), now I read some of their non-fiction occasionally, or classics (Annie Proulx, Updike ...). I have really gone cold on their fiction. It feels performative to me, anti-stories often.