✍️ Are You Selling Out?

or, Why Pride Sometimes Comes Before the Rejection Slip

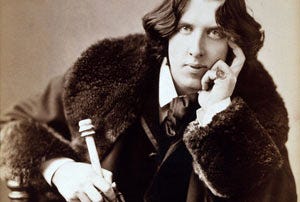

Arthur cared deeply about artistic integrity.

He had a very successful string of short stories featuring a unique character that the general public lapped up. But very shortly, he felt the writer’s equivalent of being typecast – when he tried to write different stories, too often the public turned its collective back. It got to the point when he finally killed off his character. Even that wasn’t enough to keep the public down. He was basically forced to write a prequel story and eventually brought the character back to life, creating an elaborate story as to why this character didn’t die after all.

I’m not sure he would have used these words (or if they even existed at the time…), but essentially he felt like a sell-out.

It didn’t help that Arthur didn’t think much of the writing himself. It was popular, sure. But it wasn’t literary. He wanted to write classics in the vein of Thomas Hardy and Robert Louis Stevenson. Arthur saw these writers as the pinnacles of his profession.

I understand Arthur’s angst. When I was a young whippersnapper, I cared deeply about artistic integrity. I read articles pumping up young writers and teaching them how to “stand their ground” when an editor or publisher tried to “force” changes on them.

There is a certain irony that today, Arthur’s stories – Arthur Conan Doyle and his alter-ego Sherlock Holmes – are at the very least on the same level as those “classics” and are probably more widely read.

What would he make of that, I wonder?

What the Hell is a Sell-out Anyway?!?

I think in the simplest terms, we would define a “sell-out” to be a writer who gives up artistic integrity in favour of money. But the term “artistic integrity” is a bit murkier, at least from a psychological and practical viewpoint. Writers tend to care a lot about their work. Which isn’t a bad thing of course, but sometimes it can lead to bad decisions. They hold on too tightly to their words, believing them to be almost divine inspiration, and therefore untouchable.

I remember talking about selling out and artistic integrity probably around 1995 when the Internet became a thing. Chat groups and blogs were abuzz with stories of mean, spiteful editors trying to manipulate honest, faultless writers. Nobody should tell you what to write was a common refrain. Also, Editing is censorship.

After years of reflection and experience, I came up with my own conclusion: Bullshit.

I’ll explain why I think holding on too tightly to your words is detrimental in a moment. But here are the things I want to underline first:

Our words are not the holy of holies.

Words on a page are a two-way street. You may understand clearly what you are saying in your words. Your reader may not.

That’s where editors and publishers can help. They can point out where there is a disconnect between the words on the page and the reader reading them, whether it’s logical, plot holes, unclear writing, or any number of other things.

Things go sideways for writers when they decide they don’t want to “sell out” and in turn, decide not to heed the words of well-meaning, even professional, feedback. Worse, these writers get all pissy when an editor or publisher decides they won’t publish it without the changes.

What these writers don’t get is that the editor and publisher have a vested interest in the success of the story, poem, whatever too. It’s your story, but it’s their publication. Why should they choose to publish something they believe is sub-par after the writer clearly states s/he is not willing to work with them to make necessary changes for the sake of the reader?

The short answer is: they shouldn’t.

Of course, I’m not saying that writers need to accept all suggestions. Nobody knows your story better than you, and you may have good reason to push back on suggestions. Which edits/suggestions should you reject? That comes with experience and confidence – in other words, it’s a skill you’ll learn over time.

But I do have a few ideas for you while you negotiate those treacherous waters…

How to Take Advice without Feeling Like a Sell-out

Be open to feedback. This is the hardest step. Learning to take criticism is probably the most important skill you can have as a writer after writing skills themselves. Too often, we get self-defensive and let criticism deflate us. Instead, it helps to separate ourselves from our work and see criticism as an opportunity to make the piece better. Again, it’s hard to do, but it’s worth it.

Open your eyes to new possibilities. This builds on the above point. Sometimes, we get stuck on some thing like, Joe goes to the theme park in Chapter 3, and that’s the only way the story will work. But what if someone suggests moving that to Chapter 1? Can you envision a world where that happens? I always go into receiving feedback with the idea that everything is changeable if it helps me connect better with the reader.

Consider the source. For example, a person who has never written a Haiku might not be the best person to give you feedback on your Haiku. But that’s not to say their feedback isn’t valid – especially if they regularly read Haikus. It’s a juggling act, but I’ve found that everyone has something useful to contribute. At the very least, they make you look at the piece in a different way, which usually spurs some changes.

Consider the advice/feedback. My “everything is changeable” viewpoint doesn’t mean that everything should be changed. As mentioned above, nobody knows your piece like you do. You’ve spent the most time with it, agonized over particular words, considered it from every angle. Maybe the editor/critic forgot that the main character’s car was red in Chapter 1 and it was red because it symbolized love and you wanted to reinforce that symbolism by making the volleyball red, even though volleyballs aren’t usually red, which is why they flagged it for you. On the other hand, maybe that symbolism isn’t working for the reader, which could be another reason to reconsider. Or, maybe not…

Not everyone is going to like your work. Feedback is simply impressions and suggestions from one single source. As we’ve talked about before, some people love The Great Gatsby and call it the best book ever written, and some people don’t understand why people would call it good, never mind the best. Feedback from these two different people will be, to put it mildly, dissimilar…

Remember that you have final say. Collecting feedback is important, but you get to decide what advice to follow and what advice doesn’t work for you. You also have to accept the consequences. If an editor says they won’t print it if you don’t change it, well, that’s a tough decision for you to make. Luckily, you’ll be happy to hear, that specific situation doesn’t come around too often.

Arthur Conan Doyle eventually went back to writing Sherlock Holmes stories. I don’t know if he felt like he was selling out or just became more pragmatic in his later years. Doesn’t matter. What matters is what you, the writer think about your own work. My advice is to be open to changes because more often than not, it helps you improve your work.

But of course, the whole point is, you can take that advice or leave it… lol

Key Takeaways: Getting feedback on your work and acting on it is not “selling out”. More often that not, good criticism helps you improve your work. Being open to feedback and learning over time how to incorporate it into your work can help improve the experience for your readers while you stay true to your vision.

Over to You: Have You Felt Like a Sell-out?

Do you refuse all criticism? Do you feel like feedback is an infringement on your writerly rights? Do you have other pointers for taking and incorporating feedback into your work? Let us know in the comments below!

I’ll leave you with a trailer for Killing Sherlock: Lucy Worsley on the Case of Conan Doyle, a documentary that inspired the intro to this post. (Inexplicably, PBS changed this title to the trite and boring “Lucy Worsley’s Holmes vs. Doyle”, so the title will change depending on where you watch it.)

Until next time... keep writing with wild abandon!

~Graham

PS - One of those same Laughing Foxes I talked about last post alerted me to a reality TV show for writers, Write or Flight. I put together what I believe was a strong application – I’ll find out by next post whether or not I made the longlist… Fingers crossed – I was made for this type of competition!

email me if you get lost.

Selling out for money? One wishes, lol. Most editors I've dealt with have made the work better, but I've also met incredibly stupid ones that have brought me close to the boiling point. That's where diplomacy matters. In other words, not rejecting the comment outright with a huff but finding a way around it. Although some things NEED to be rejected outright! I'm married to a writer, a very very good writer, and he's my first reviewer. I don't accept all his comments but they always make me think ... and being married, it's not a good idea to fight for a word or a sentence! Gotta take the long view here.

Love it! And I can see how this relates to any careers and really any parts of our lives. It is not always easy to see the difference between misplaced ego, boundaries and goals. I have been caught more than once!