Becoming the “voice” of a generation is one of those things that we writers aspire to. None of us speaks this truth out loud. We may not even think it consciously to ourselves. But we do want our words to be loved. We do want, inwardly or outwardly, writerly merit badges like winning the Booker Prize and reaching millions of readers. What shinier merit badge is there than writing something that shakes a generation?

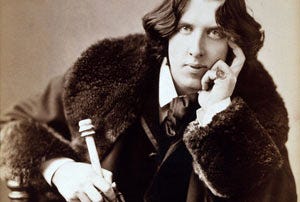

One writer I admire comes to mind. He was born in a country that no longer exists, who lives in Canada, but who may be just at home (and as welcome) in the US. This writer became the voice of his (my) generation I think partly out of a need to find his own voice as a fiction author.

Funny story – he was a fairly accomplished magazine writer who went out to the desert to write his first non-fiction book, but he came back with a novel. Rejected by the publisher who sent him, it found a home at St. Martin’s Press, which published his thin tome on March 15, 1991. From almost that moment on, the author started spending the rest of his life rejecting any notion that he spoke for anyone other than himself.

I imagine being the voice of a generation is something akin to being famous: sounds good, but when you can’t go for eggs without being accosted by a million fans, the glammy, glittery veil quickly falls. Still. There has to be a part of him deep down that revels in not just tapping into the zeitgeist of the time, but electrifying it. Unifying a generation that by the very name he popularized – X – was ununifiable. Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture by Douglas Coupland did just that.

However, that’s not the point of this post. In order to be the voice of a generation, you first need to have a voice. That’s what I want to talk about today.

The Poetry Part of You

First of all, what is voice? There are many descriptions out there. Voice can involve your style of writing. That includes things like the words you choose to use, the tone (playful, academic, formal, sarcastic, etc.), the way you make the reader feel, and other related characteristics. Some include “perspective” in this list as well.

However, one key point left out of many definitions is perhaps the most important part of voice: your control and confidence as a writer. That’s what grabs readers and keeps them. We’ve all read writers who seem tentative, unfocused, disorganized. We’ve also (thankfully) read the opposite: writers who pull you into the story, gain your trust, and take you willingly on an adventure. Generally speaking, the stronger the voice, the more likely we’ll buy into what the writer is saying.

Douglas Coupland has a great quote on voice himself:

When you write, it's just a much more crystalline, compressed version of the voice you think with – though not the one you speak with. I think your writing voice is your laser-guided missile. It's the poetry part of you.

Bolding mine, because I love that sentiment. Who are you as a writer? What defines your voice? What is the poetry part of you? Most of us don’t have an answer to that. Some lucky writers have an inkling. But that takes years of writing and feedback.

I’m not going to dwell on definitions too much here. You could read a dozen books on voice and never have any agree. But just because it’s verging on the ineffable does not mean it’s not important. Let’s say it’s like art: it’s difficult to define voice, but I know it when I see it. (For the record, I think “It’s the poetry part of you” is as good a definition as any, even if the definition is semi-ineffable in itself.)

No, instead of definitions, let’s dive into how to find our own voice.

Discovering Our Poetry

“Find” our own voice – I use that word deliberately. For the most part, I do believe that our voice – our poetry – is discovered, not created. There are famous examples that seemingly contradict this, such as Hemingway toiling for decades to hone his style. I’d say this is still an example of discovery. He may have had a better handle on what he was looking for, but it still took him years to find it.

Remember: voice is important because it’s what connects with readers and gives them confidence that you’re taking them somewhere they want to go.

Here are some ideas about how you can discover your own poetry:

What’s your writing style right now? As pointed out above, we may not know exactly. But in doing this exercise, we at least reveal what style we want it to be. That’s a start.

Read related. Immerse yourself for a few weeks or months or years in writing like your own or that you want to be your own. Read with a careful eye, noting what works well and what you love. Work on adapting their style(s) in your writing.*

Search out books and blog posts about how to write that style. You can find anything online these days. Search out “how to write like Hemingway” and you’ll get a ton of answers. Glean tips from these sources.

Write with wild abandon. As with many aspects of writing, you find your best gold when you’re not trying too hard to find the “right” words every single second. Write a story or even an account of your day in just the way you would tell someone, worrying about the account you’re telling and not the words you’re using. The faster you write, the less you’ll second-guess yourself.

Experiment with your writing. Try a style you’ve never thought about before. Don’t feel locked in with the kind of writing you’re doing now. Try swearing if you don’t swear; try not swearing if you do. Get loopy if you’re serious; write a dissertation if you tend to the trippy side of narrative. Satire, romance, edgy, flowery. Try anything and everything at least once and see how it looks on you.

Get feedback. This may be trusted friends and family at first. You can also join a writing group that critiques each other’s work. If you remember to put on your thick skin, you can get valuable feedback on what works and what doesn’t in that writing.

Journalling can help. Journals are great places to experiment and also get you into the habit of writing daily or regularly. (See below.)

Write about something you hate. Read this post from Gotham Writers, in which the author talks about the passion that comes out when you write about something you hate. (Tellingly, although the author agrees that Voice is somewhat indefinable, his definition differs from mine.)

Sow now, reap later. Romaine lettuce doesn’t grow in a day. You’re not going to get instant results, no matter what approach you use. Although you can help it along by consciously trying to develop your voice, it will still take time to evolve. So be patient and…

Write often. This is the best and surest way to develop your voice.

Key Takeaway: Voice is difficult to define. Douglas Coupland calls it the “poetry part of you”. Finding your voice can take time, but it’s important to start developing it early on. Imitating others, getting feedback, and writing every day can help you find your voice faster.

Over to You – What’s Your Writing Voice?

Have you found it yet? Are you still searching? Personally, I believe I have found my voice, but I’m always working on improving it.

I leave with an interview with Douglas Coupland from 1991, the same year Generation X was published. You’ll see how he’s already dodging being the voice of a generation – I find it all fascinating. But then, we writers tend to dodge the spotlight anyway, don’t we?

Until next time, keep writing with wild abandon!

~Graham

email me if you get lost.

I really enjoyed this one Graham, likely because it’s a question I think about quite a bit. My own Substack has been an attempt to find the voice that is most suited for me, and I think I’ve done so in the last six or nine months, but god, how to define it? I don’t know. That’s a very good question and I may follow up with you on this one.

I think I took a shortcut, I just started writing poetry itself. 😀