✍️ Is Your Writing Pretentious?

or, Why the Bean Mouth Style Matters

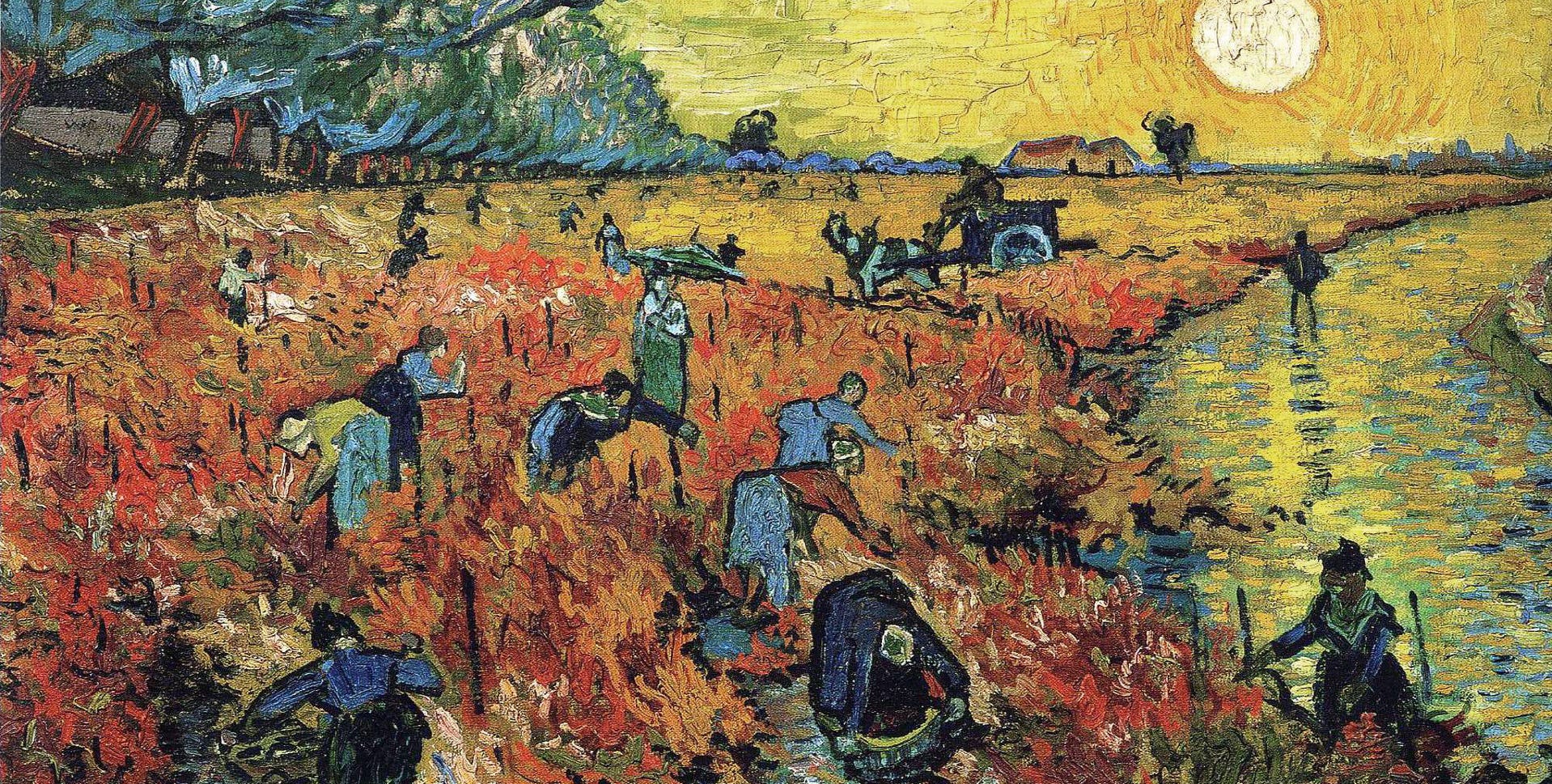

Today, Van Gogh’s paintings sell in the millions of dollars. But when he was alive, he sold just one: The Red Vineyards near Arles (for 400 francs or about CAD $2,800 in today’s money).

Why?

I stumbled across this blog post by artist and critic Eric Wayne about that painting and Van Gogh in general. Today, he’s considered to be a major influence in Western art. Back then, Van Gogh’s art came across as chunky and amateurish, and the general consensus was that he was a pretentious ass-hat. Thick, blotchy lines, over-saturated colours, and rather mundane scenes (like, peasants in a vineyard instead of a great battle or divine supper) made him a sensationalist – think Andy Warhol without the 15 minutes of fame in his own lifetime.

In fact, Wayne suggests that Van Gogh may only be famous today because he got famous other ways – through his mental illness, through cutting off his ear, through his death by suicide. So, his paintings are popularized by association, much like a lock of Marilyn Munroe’s hair has associative value rather than intrinsic value. After all, a lock of hair is only a lock of hair.

But are Van Gogh’s paintings works of art? If their value is intrinsic rather than associative, why didn’t people see it back then?

This is a topic I’ve come across in writing, too. Things like “purple prose” and even calling your writing “art” trigger accusations of pretentiousness. Well, la-di-frickin-da.

It makes me wonder though: what makes art “art” rather than “pretentious ass-hatting”?

I have a theory…

Pretentious = Bad, but What (and Who) Defines “Pretentious”?

So what does “pretentious” even mean in the arts? Like the definition of art itself, it’s elusive. Pretentiousness is in the eye of the beholder.

One beholder, Eric the Gray, says this:

I can declare (with absolute certainty) that wordy, pretentious writing is bad. If a sentence has 90 stuffy words when it only needs 25 short ones, it’s bad writing. If a writer is trying to impress us with his expensive-looking vocabulary instead of informing, entertaining, or touching our souls, it’s bad writing.

He holds up minimalist author Elmore Leonard (Get Shorty, among many others) as the epitome of great writing and the antithesis of pretentiousness.

But let’s go to one of my (ahem) go-to authors: F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Dartmouth Review agrees that he is “an artist” rather than “pretentious” – though the implication is that others might see him that way.

Leonard was a great writer. Same with another famous minimalist, Ernest Hemingway. However, the lack of “purple prose” and therefore the lack of perceived pretentiousness was an artistic choice, not an intrinsic ability to write clear, simple sentences. Hemingway worked on his pared-back style his whole life – there was nothing natural or intrinsic about it.

And here’s the thing: Fitzgerald worked on his own prose style his whole life, too. It’s my belief that any accusations of pretentiousness against Fitzgerald are by definition false. You may not like flowery, poetic prose, just as I’m not a fan of pared-back, simple sentences. That doesn’t intrinsically make Fitzgerald’s writing style pretentious or bad.

So what does?

Art is as Much about Effort as Result (Hear Me Out…)

Coincidentally, during the writing of this essay, I read an article on the CBC website about why the latest Pixar film Elio bombed so badly. Apparently, the chatter on the intermewebs is that the biggest reason Elio fails is that it uses the “bean mouth” or “CalArts” style of simplistic animation, which many of the audience look down upon as lazy and cheap.

In the article, animation journalist John Maher pooh-poohed that notion, stating that, "If that's really what we are condemning art for at this point — we don't like the style so we're not even going to bother to understand the substance — we're in trouble." CBC writer Jackson Weaver found that insight to be so important that he closed the article with it.

Coming as that article does during the writing of this piece, I’m actually inclined to disagree. Shouldn’t enjoyment be part of the art experience? Shouldn’t beauty (in whatever form it takes) be intrinsic to what the beholder considers to be art? If the audience reacts negatively to “bean mouth” for laziness or ugliness or any other reason, isn’t that valid? (I wrote about how James Cameron delayed Titanic by about six months, in part to get out from under the negative press. Spoiler alert: it worked.)

Similarly, Van Gogh’s thick, crusted lines were seen as lazy and pretentious in his time. We see them differently now. Art critics know how much work he put into developing his style, just as the one movie critic saw past the bean mouth style to the movie below.

Except that…

Billy Joel taught us that you can’t dress trashy ‘til you spend a lot of money. John Lennon opined that if you go around carrying pictures of Chairman Mao, you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow. Style does inform substance – at least on the part of the reader or audience.

Here’s how I differentiate between art and pretentiousness in writing:

If you take the art seriously (like, spending time honing your craft), that’s admirable – that’s a step towards art. If you take yourself too seriously (like, trying to impress people with pictures of Chairman Mao), that’s pretentious.

Passionate honesty leads to art. Lazy pfaffing leads to pretentiousness. Art is as much about effort as it is result.

Aye, but there’s the rub. “Keeping it real” doesn’t magically ward off all accusations of ostentatious pomposity. Take, for example, the fact that if any North American pronounces Van Gogh’s name the real way (van goff), you come off as a pretentious ass-hat yourself. Really, anything you do can be called pretentious. (I mean, how pretentious was it of Hemingway to believe he could invent a new, unpretentious writing style?)

I’ll say it again: pretentiousness is in the eye of the beholder. The best you can do is be true to yourself.

Key Takeaway: Art is as much about effort as result. If you take your art seriously rather than yourself, you’re moving in the right direction (even if you don’t call your writing “art”). However, that won’t necessarily stop others from calling your writing pretentious. But really, who cares? Be true to yourself.

Over to You: Do You Have Grandeurs of Pretensiousness?

Are you worried about being too pretentious in your writing? Do you find others’ writing to be pretentious? Is pretentiousness something you’ve ever thought about when it comes to writing? Let us know in the comments below!

I’ll leave you with a video about Elmore Leonard’s tips for writing. Scroll down below.

Until next time... Happy Canada Day to all who celebrate and keep writing with wild abandon!

~Graham

email me if you get lost.

For people who don't read, "writing a book" by itself comes across as pretentious (they're likely to have the same opinion about painters, sculptors, and composers). As to 'poetic" vs "minimalistic", it comes down to enjoyment. I can get transported by a long, literary, heavy with atmosphere passage from Tana French, as well as a hilarious and punchy Carl Hiaasen chapter. I've also read minimalistic prose that made me yawn. You can be too dry. I don't think Fitzgerald is pretentious, by the way. The big sin is to be boring. Who said that?

Related: I struggle with marketing labels for my novel(s), and also comp titles.

I cringe to describe my novel and WIPs as “literary,” because that sounds SO pretentious. And also, I think they’re more accessible than many books with that label, but my work is less commercial than others’ books.

(And also, my novel does talk about Why Do Bad Things Happen to Good People and the book of Job, which aren’t generally elements of beach reads.)

Which also doesn’t really matter to my own sense of “doing work that’s important to me” (which is how I am lucky enough to choose projects)—except that publishers like it when readers find books.

Which means accurately describing them so that readers are excited about what they’re getting and are delighted when they dive in. Which means comp titles and labels.

Which I’m trying to better learn about so I can write the book I want to write and be a good partner for a publisher. Not that I’ll add something randomly popular to my work for marketing ease—like dragons (for example) (although … hmm).

Which attention to the market is viewed by some artists as “selling out.” Which I understand and see differently.

I just flashed back to the high school question about the Beatles, “are you John or Paul?” Meaning the deep artist, courting controversy, or the popular sellout. I also think there’s room for a George, a uniquely curious musician following his interests, and a Ringo, who’s sitting in the back singing about octopi (pretentious sounding plural) in gardens and holding the beat so everyone gets along.