Recently, I was in an online workshop. The presenter – we’ll call her Karen, because that’s her name – mentioned an idea I just love:

“We write in order to understand what we are writing.” Gorgeous. And exactly right.

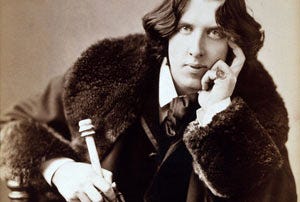

More on that in a moment. But first, let me tell you about Karen, because it figures in. Karen is one of those writers who started writing at an early age. She took Hemingway’s advice long before she heard it, I’m sure: “In order to write about life, first you must live it.” She travelled to Thailand, Spain, Greece, and other places. Not as a tourist or even a traveller, but as someone who immerses herself in the cultures for months at a time. We talked about Living La Vida Artistica recently; Karen has taken that vida to a whole new level with an adventure chaser on the side.

If that’s not enough to make you jealous of her lifestyle, she’s wildly successful, too. Karen is an accomplished poet, non-fiction writer, and fiction writer of short stories and novels – the EGOT of the literary world (SPNN?)

In fact, she develops her ideas in that order, at least some of the time. “First I write poetry, then I write non-fiction, then I write a novel,” Karen said in an interview. It’s a fascinating process that I’ve never heard of before, but makes total sense when you say it out loud.

And it also circles back to her quote: We write in order to understand what we are writing.

Many of you have guessed that I’m talking about Karen Connelly (or Kaz, as she often goes by), a Canadian writer who has won the Governor General’s Award in Canada among other distinctions, and who I’ve had the pleasure of meeting on a few occasions. I think if we take a closer look at her writing approach, we can all learn something about filling that blank page.

One Way Karen Connelly Learns What She’s Writing About

I was going to talk about the “Karen Connelly Process” but that’s a little too formal and perhaps implies that’s how she always writes. I’m not sure that’s true. But there is one solid example of her early writings that does encapsulate the concept of writing to learn what you’re writing about. First she published “The Small Words in My Body” (her first book of poetry), followed by “Touch the Dragon: A Thai Journal” (her non-fiction memoir), and finally “The Lizard Cage” (her first novel). I wouldn’t call it a trilogy, but they definitely represent a connected body of work. I’d say too that this approach is part of what makes Karen’s fiction seem so real.

A couple of caveats. I don’t want to suggest that these works need each other to be relevant. They all stand on their own. Similarly, I’m not even sure Karen tried to connect these works in any conscious way. It’s possible she noticed this writing approach upon reflection.

But regardless, there is a pattern here that we can learn from.

Poetry – Karen started with the emotional, which makes total sense to me. After all, emotion is the heart of fiction writing, in all senses of the word. (For me, it’s also the hardest part of fiction writing.) So to get those emotions down on paper through poetry captures the feeling of the moment.

Memoir – The next step, non-fiction, concentrates conveying information rather than pure feeling, the facts and information that make a setting and situation real.

Novel – What is fiction but a careful mix of information and emotion? Information drives the outer story – the plot – while emotion drives the internal struggle.

I’ve sub-headed these points as “Poetry, Memoir, Novel” but of course you can slip in different types of writing, such as “Song Lyric, CNF, Short Story” or “Haiku, Essay, Novella”. The types are unimportant. It’s clear though that there are huge advantages to working out both the emotional and the informational aspects of a story before writing it down in a work of fiction.

However, the main point I want to make is that Karen doesn’t expect she’ll sit down and churn out a wonderful, spell-binding novel in one go. When we decide to write to learn what we’re writing about, everything changes. This is one of the key secrets I want all writers to know that would prevent 99% of so-called writer’s block. Don’t worry about what you’re going to write. Starting writing, and figure out what it means later.

Easier said than done? Sure. So I’ll include an approach to make it easily done, too. I call it EFFing writing.

Just EFFing Write It

EFFing writing is a technique for taking creative risks and overcoming the fear of the blank page. It’s inspired by Karen’s writing-to-learn-what-we’re-writing process: Emotion, Fact, Fiction (EFF). Now, we aren’t writing three whole books here by any means. But fiction writers and even creative non-fiction writers who are stuck can tap into this on a smaller level to help them fill their blank page.

The next time you think, “I have no idea what to write about”, try this:

Ray Bradbury famously made a list of all the things in life that interested him – and by extension, things he’d like to write about. Make your own list.

Did something in that list spark a memory or a particular feeling? Write a poem about it, concentrating specifically on how it makes you feel. Or just choose whichever strikes your fancy.

Write about that thing on your list in factual detail. Do some research, if necessary. You could write these facts as an essay, bullet points, random notes – doesn’t matter. Just get the facts down.

Take the feelings from you poems and the facts from your research and create a story. Hopefully, just turning over in your mind what you’ve written so far will prompt a plot. But if not, write a scene or even a vignette snippet. Keep writing until something sticks.

The beauty of EFFing writing is that you can use it in the middle of something you’re stuck on, too:

Write a poem about the scene you envision (however vague that vision), whether it’s fiction or non-fiction. How does it make you feel? Don’t settle for “sad” or “happy” or whatever. Get complex. Some of the most poignant moments in our lives are when we’re feeling an array of emotions in the same moment, like watching your kid drive off to university in his own car. Brené Brown’s Atlas of the Heart helps me find some unique blends of emotions.

Write a laundry list of details about the scene. What setting? What time of day? What colour eyes? What brand of snow tire? What catches your eye most about that crowbar sitting abandoned in the corner? Don’t think too hard about any of this. Just picture the scene in your head and write down what you see – or what you think you should see.

Combine the laundry list with the emotional verse. If there are particular turns of phrase or charged language you like from the earlier pieces, do not be afraid to use them – they’re yours for the taking! You should see the scene come together like putting on a pair of 3D glasses, more vivid and with more depth than you did before.

Key Takeaways: One of the reasons for so-called writer’s block is that we don’t know what to say. Worse, we expect that we should. Instead, write in order to understand what you are writing. Start with the emotion, identify the “facts” of setting, plot, details, and combine the two to create something brand new.

Over to You: Does EFFing Writing Work for You?

Give it a try the next time you’re stuck, and then please do come back and share in the comments below. Did EFFing writing work for you? Anything you’d change? Any new insights you learned?

I tried it myself last weekend, and was surprised at how much clearer I was able to see a scene I was working on. It also helped me add more detail – sensory detail, like the cold and the wet of an early morning, which I didn’t have enough of before. I’m happy with the results! I went in directions I didn’t expect, and although it doesn’t work as a complete poem (it was never supposed to), it did give me a better emotional sense of the scene.

I’ve shared that “poem” (I can’t stress enough how loosely I’m using that term…!) below so that you can see how easy it is to do. This is mostly unedited stream of consciousness, though I did play with the words a bit in a couple of places. It took me about 10 minutes to write. All I did was start with an idea of the scene and the current mindset of the main character. Then, I spit out some words without thinking about them. I highlighted lines that jumped out at me that I may or may not be able to incorporate later…

I leave you with a YouTube video (YouTube audio?) of Karen Connelly reading from one of her books of poetry, This Brighter Prison.

Until next time, keep writing with wild abandon!

~Graham

email me if you get lost.

Great stuff, Graham. Thanks.